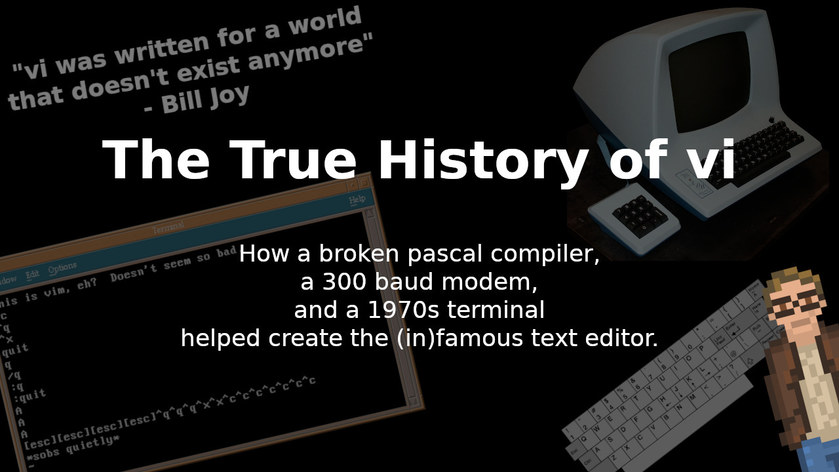

Earlier this week (August 3rd, 2023), Bram Moolenaar, creator and long-time maintainer of Vim passed away. The following article -- originally published earlier this year -- has been updated to include a brief history of Vim.

Everyone who has spent any time with UNIX or Linux knows about vi — the ubiquitous text editor that seems to have existed since the dawn of time itself.

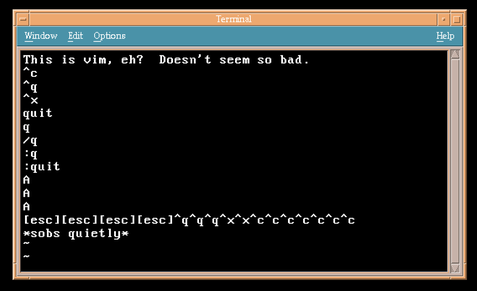

Likewise, there are better than even odds that the first time you ran vi (or vim, which is based on vi)… you got stuck and couldn’t figure out how to exit the gosh-darned program.

Don’t feel ashamed. It’s a right of passage.

What follows is the story of that much loved — and much hated — text editor. Where it came from, who created it, how it was almost very different, and why on earth it is the way it is.

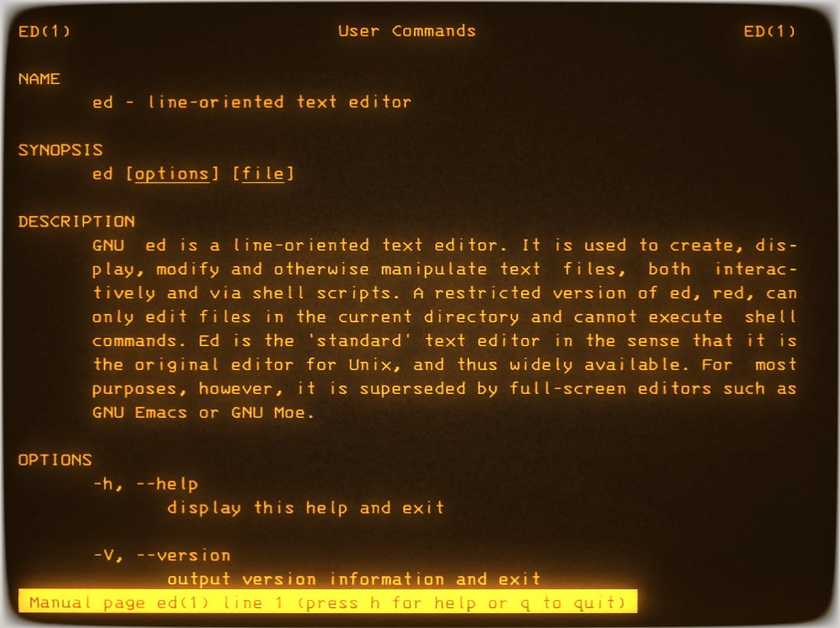

It all started with ed

As with so many stories in computer history, the tale of vi begins long before vi, itself, ever comes into existence.

Our story begins in August of 1969, at AT&T Bell Labs.

There, Ken Thompson was beginning work on what would become UNIX. At that time it was a barebones system, running on a PDP-7, consisting of only three little components: an assembler, a shell… and a simple text editor known as “ed”.

Ed, which is (obviously) short for “editor”, is a line-mode text editor — meaning you edit one line of text at a time. A process which can drive any person to the brink of madness.

Historical Side Note: The design of ed was inspired by QED (which is short for “Quick EDitor"“) — a similar line-mode text editor created for the Berkeley Time Sharing System in the mid-1960s — and was re-written for MULTICS (the precursor to UNIX) by Ken Thompson. So it seems natural that, when Thompson needed a basic text editor for UNIX… he would base it on the design of QED, which he was already so familiar with.

Ed quickly became the defacto line-mode text editor for UNIX — remaining a part of the POSIX standard to this very day.

A wild Pascal appears

A few years later, in 1975, Ken Thompson went to Berkeley (the University of California) and built a Pascal compiler for UNIX.

There, his Pascal compiler came to the attention of a student at UC Berkeley… Bill Joy. The man who would go on to create vi.

From Bill Joy’s 1999 interview with Linux Magazine:

“What happened is that Ken Thompson came to Berkeley and brought this broken Pascal system, and we got this summer job to fix it. While we were fixing it, we got frustrated with the editor we were using which was named ed. ed is certainly frustrating.”

As with so many stories in the advancement of software… work begins when a programmer gets frustrated with existing software.

“We got this code from a guy named George Coulouris at University College in London called em - Editor for Mortals - since only immortals could use ed to do anything. By the way, before that summer, we could only type in uppercase. That summer we got lowercase ROMs for our terminals. It was really exciting to finally use lowercase.”

Anyone who has used ed for any sizable project knows how frustrating it can be to use. While ed has many strengths (and is great for usage via shell scripts) editing large portions of text is not one of them.

Now, with inspiration from the “em” text editor, things really kicked into gear.

From the August 1984 issue of UNIX Review:

“So Chuck (Haley) and I looked at that and we hacked on em for a while, and eventually we ripped the stuff out of em and put some of it into what was then called en, which was really ed with some em features. Chuck would come in at night - we really didn't work exactly the same hours although we overlapped in the afternoon. I'd break the editor and he'd fix it and then he'd break it and I'd fix it. I got really big into writing manual pages, so I wrote manual pages for all the great features we were going to do but never implemented.”

Put simply… ed + em = en. Sort of.

Also, I love the whole “I wrote manual pages for all the great features we were going to do but never implemented” part. Been there!

Modems and Terminals and vi weirdness

Back to the 1999 Linux Magazine interview:

“I don't know if there was an eo or an ep but finally there was ex. [laughter] I remember en but I don't know how it got to ex. So I had a terminal at home and a 300 baud modem so the cursor could move around and I just stayed up all night for a few months and wrote vi.”

ed… em… en… [eo… ep?]… ex… then, finally, vi.

That is how we got to vi. The family tree of vi, if you will.

Worth noting here that “vi” is short for “visual mode of ex”. Running “vi” is literally a shortcut for launching the “ex” text editor directly into the full screen “visual mode” instead of the default “line mode”

In fact, if you were already running ex, you could enter the “visual mode” by entering the vi command.

And, what’s that? Vi was programmed on a 300 baud modem?

Seriously. Considering a 300 baud modem is 1/4th the speed of a 1200 baud modem (which transmits text slower than most people can read it)… this explains much of the design of vi.

“It was really hard to do because you've got to remember that I was trying to make it usable over a 300 baud modem. That's also the reason you have all these funny commands. It just barely worked to use a screen editor over a modem. It was just barely fast enough.”

Here, Bill Joy compares the reasons behind the design differences between emacs and vi:

“The people doing Emacs were sitting in labs at MIT with what were essentially fibre-channel links to the host, in contemporary terms. They were working on a PDP-10, which was a huge machine by comparison, with infinitely fast screens.

So they could have funny commands with the screen shimmering and all that, and meanwhile, I'm sitting at home in sort of World War II surplus housing at Berkeley with a modem and a terminal that can just barely get the cursor off the bottom line.

It was a world that is now extinct. People don't know that vi was written for a world that doesn't exist anymore.”

Short, single character commands in vi kept things usable even of that slow connection.

As Bill Joy put it, “vi was written for a world that doesn't exist anymore.”

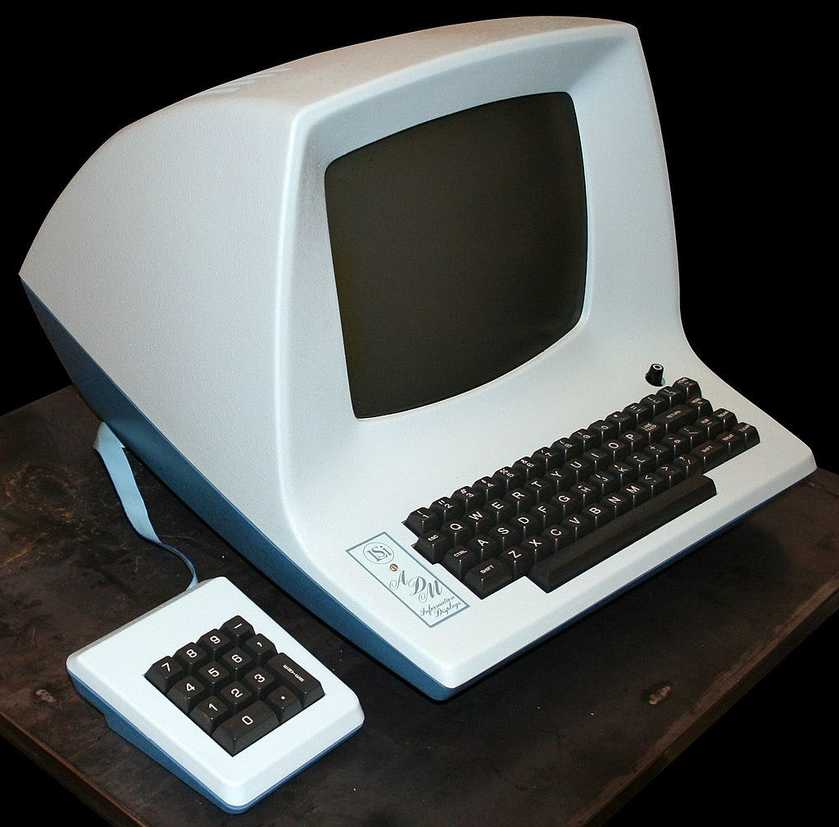

While the hardware limitation of the 300 baud modem had a significant influence on the design of vi… arguably the terminal (and keyboard) being used by Bill Joy had an even bigger impact.

That terminal: the ADM-3A built by Lear Siegler.

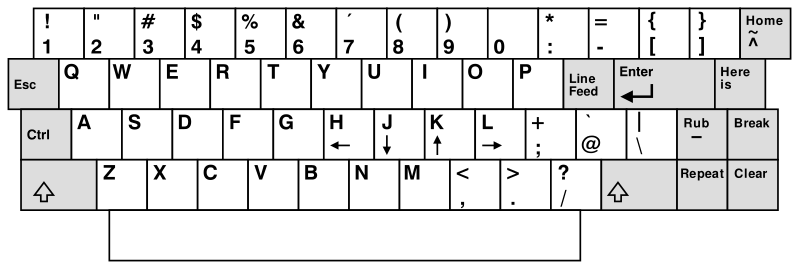

For example: Why does vi use H, J, K, and L for cursor movement? Because, on the ADM-3A, those keys doubled as the arrow keys.

You’ll also note that the Escape key is where the Tab key is on most modern keyboard. That’s why Esc is the vi mode switching key… it was, on that keyboard, easy to hit without moving your left hand off of the home row.

And, despite common keyboard layouts no longer being like this, vi stayed this way.

Vi almost changed significantly

A fun little sidenote: Bill Joy almost added multi-window support and other features… but he didn’t have backups of his code. And, as is the way, he lost that code.

“I was in the process of adding multiwindows to vi when we installed our VAX, which would have been in December of '78. We didn't have any backups and the tape drive broke. I continued to work even without being able to do backups. And then the source code got scrunched and I didn't have a complete listing. I had almost rewritten all of the display code for windows, and that was when I gave up. After that, I went back to the previous version and just documented the code, finished the manual and closed it off. If that scrunch had not happened, vi would have multiple windows, and I might have put in some programmability - but I don't know.”

Yep. We were this close to vi being quite different in those early days.

But the source code got “scrunched”.

Which is a technical term. I think.

Vi… forever

In May of 1979, Bill Joy — who was also the driving force behind BSD — released the first public version of vi (the visual mode for the ex text editor) as part of the 2nd release of the Berkeley Software Distribution (2BSD).

While, at this point, BSD was not yet a full operating system — it was an archive of a few pieces of software for UNIX — this was the launching pad for what would become one of the most famous (and infamous) text editors ever created.

While vi may have initially only been distributed to a mere 75 people (as part of the 2BSD archive)… it would go on to become a standard of POSIX, distributed on nearly every UNIX-alike system for the last 40 years.

More likely than not, people will be struggling to escape from vi another 40 years into the future.

Heck. A million years from now only three things will remain: cockroaches, Hostess Twinkies, and vi.

All because Bill Joy used an ADM-3A terminal on a 300 baud connection to build a text editor to fix a broken Pascal compiler.

Not too darned shabby for a mode of a text editor written for a world that doesn't exist anymore.

The Story of Vim

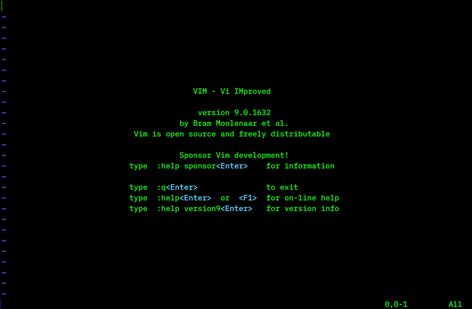

As popular -- and historically significant -- as vi is... one of vi's clones is, arguably, even more widely used: Vim. Linux users regularly vote for Vim as their favorite text editor (or, at least, one of their favorites).

The path from vi to Vim wound through Unix, Atari ST, and Amiga systems... and back again.

- In 1987, a man named Tim Thompson created a vi clone (from scratch, with no code copied from vi) for the Atari ST. He called it STEVIE (which stands for ST Editor for VI Enthusiasts.)

- In 1988, STEVIE was ported to OS/2, Amiga, and UNIX by Tony Andrews.

- Later in 1988, Bram Moolenaar took the source code for the Amiga port of STEVIE and began modifying it to meet his own needs. The result was Vim (or "Vi IMitation"). Because it wasn't a fork or port of Vi... but an imitation.

- Moolenaar would continue to work on Vim for the next few years, eventually making the first public release in 1991.

Eventually (in 1993), the "Vi IMitiation" name was changed to "Vi IMproved"... and Vim was ported to an incredible number of platforms -- from UNIX to DOS to Haiku.

And it still uses those same, crazy, vi default keys... inspired by the ADM-3A.