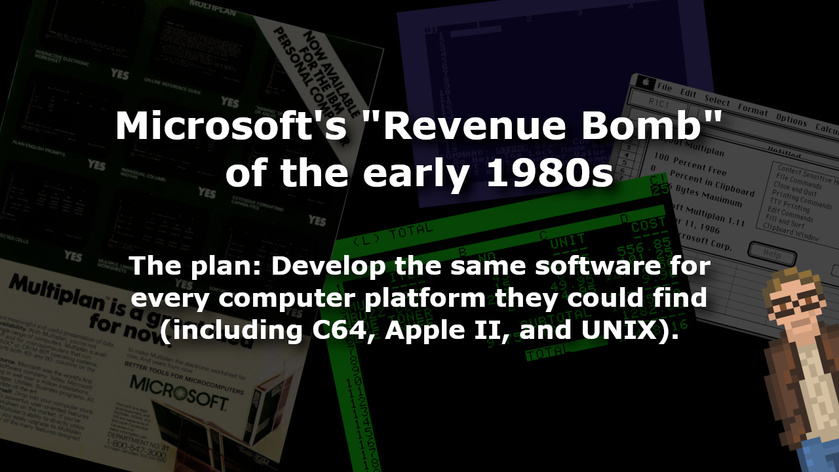

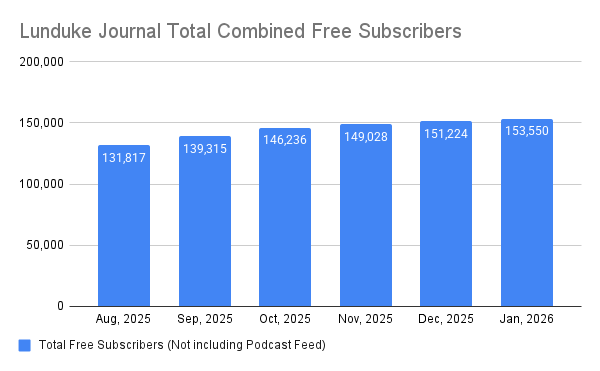

It is fascinating to look back at the way Microsoft’s approach to the software industry has changed over the years.

Case in point: In the early 1980s, Microsoft was attempting to make software for every microcomputer they could find. This was an effort they called “The Revenue Bomb”.

Multiplan: The first “Revenue Bomb” software

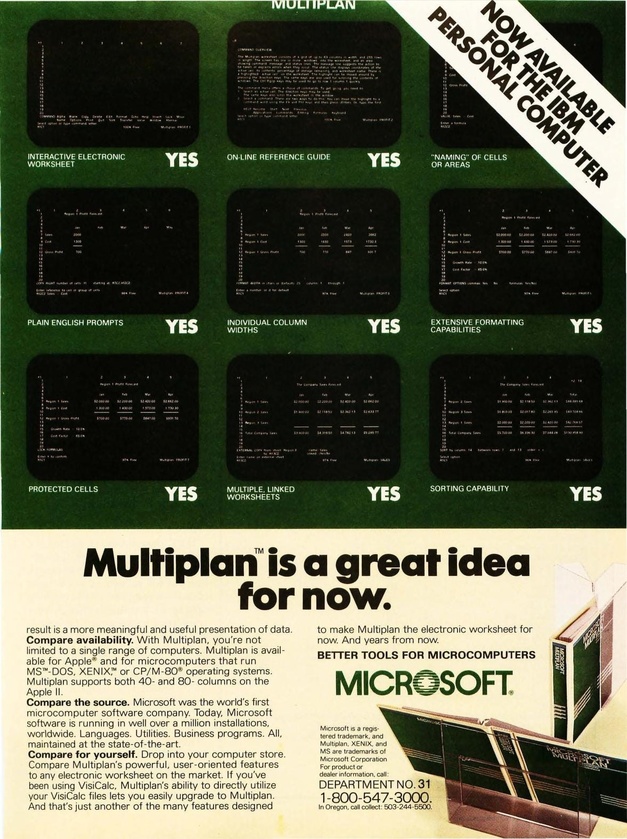

In 1982, Microsoft released a new spreadsheet program which was envisioned as a direct competitor to VisiCalc (the first commercially successful spreadsheet software).

Initially, that new Microsoft Software was called “Electronic Paper” (aka “EP”). The idea was to unseat VisiCalc by doing something truly impressive: Releasing Electronic Paper for as many computer platforms as humanly possible.

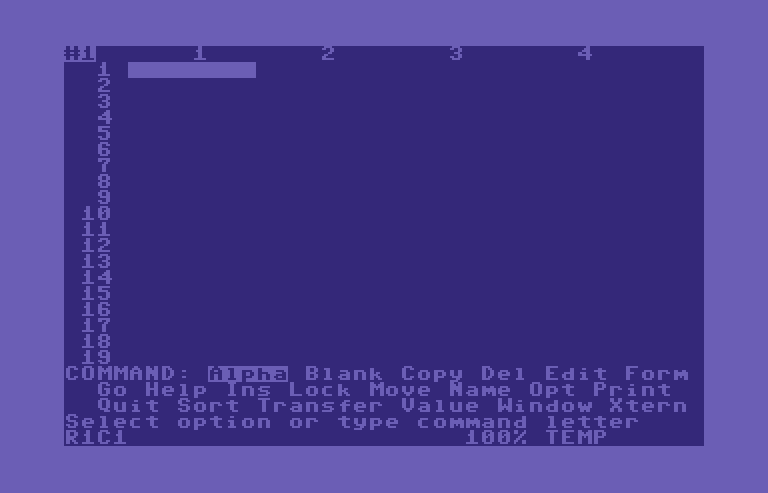

Microsoft was — at least in the early days — a very “multi-platform” computer company. Developing core operating systems and BASIC implementations for a wide variety of platforms (including Commodore 64, Apple II, Tandy, and so many others). Heck, they even made hardware for the Apple II.

In order to accomplish this task -- of releasing for such a huge number of platforms -- Microsoft developed a P-Code C compiler which they could then, in turn, port to a number of existing 8-bit platforms… all without needing to make any (substantial) changes to the core code of Electronic Paper itself.

P-Code (or Portable Code) is a type of machine code that was intended to run within a virtual machine (to one degree or another). If you could port the underlying virtual machine to a new platform, the P-Code compiled software could (in theory) simply work “out of the box”.

By the time the first version of Electronic Paper was ready to ship — initially for the CP/M operating system (from Gary Kildall’s Digital Research) — the name was changed to “Microsoft Multiplan” (or “MP”)… and Microsoft was off to the races.

Over the years that followed, Microsoft ported Multiplan to as many platforms and operating systems as they possibly could… thanks, in very large part, to their “P-Code written in C” approach.

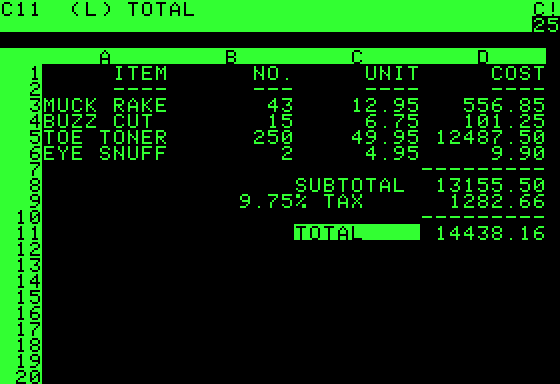

Multiplan was everywhere in the 1980s.

CP/M, Apple II, the Macintosh, Commodore 64, DOS, Xenix / UNIX, MSX, the TI-99/4a, the TRS-80 (various models), and even the Thomson TO9+.

Yeah. When I say Multiplan was everywhere… I mean it. It was almost hard to find a computer platform that did not have a version of Microsoft Multiplan available.

The man behind “The Revenue Bomb”

This strategy of releasing Multiplan for so many platforms was not accidental. It was a plan laid out by Charles Simonyi, the head of Microsoft’s application software group.

The developer of the P-Code compiler, Richard Brodie (who would go on to develop the first version of Microsoft Word), described it this way:

“Here's how the Revenue Bomb worked. You would list all the different business products that Microsoft would develop on the horizontal axis. On the vertical axis, you would list all the different personal computers that were coming out from the dozens of hardware manufacturers. The p-code C compiler, which I named "CS" and which was used for more than ten years to develop Microsoft application software, would allow us to create separate versions of each product very easily for each of the different machines.

What we didn't realize -- nor did most people in those days -- was that there wouldn't be dozens of different PC architectures competing for the market. There would soon be only two: IBM's and Apple's Macintosh. But CS gave Microsoft the upper hand for many years in developing Mac and IBM applications hand-in-hand.”

Using Brodie’s P-Code C compiler, the task to develop Multiplan fell to a programmer, recruited from MIT, named Doug Klunder. As Brodie describes it:

“But Charles's mission was to compete against the surprisingly successful VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet program. He was to develop Microsoft's spreadsheet, a project code-named "EP" (for "Electronic Paper") and later marketed as Microsoft Multiplan. That task he entrusted to Doug Klunder, programmer extraordinaire, who would go on to lead the development of the unmatched Excel after Multiplan's lukewarm market reception in the face of Lotus 1-2-3.”

Ultimately, Multiplan ended up being only mildly successful — while it sold well, it was dominated in the market by Lotus 1-2-3. Microsoft shifted efforts and focused on developing the new “Excel” software only for Windows and Macintosh.

By the end of the 1980’s, Microsoft scrapped the “Revenue Bomb” strategy entirely… opting to focus the bulk of their office software efforts on the IBM PC Compatible market (primarily MS-DOS and Windows) and the Macintosh market.

Still...

It is amazing to look back at Microsoft’s approach in the early 1980s: of bringing software to as many platforms as they could possibly muster.

There’s something awesome about that.

What would the modern computer industry look like had “The Revenue Bomb” approach been more successful? Would there be more viable computing platforms?

Hard to say. But, it sure is fun to dream about…